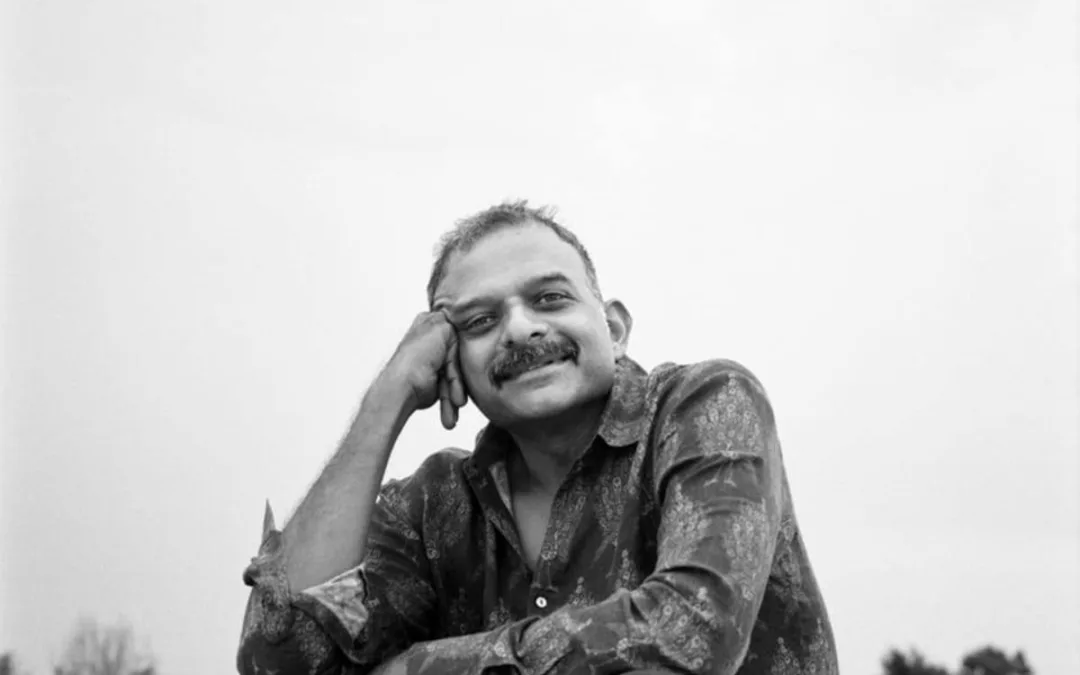

I hope T M Krishna does get to give his Sangita Kalanidhi oration. These speeches have not been momentous, barring a few times.

One can recall Balasaraswati’s 1973 speech that, in and of itself, seemed typical. But, just by recounting her formative years and her influences, she subtly drove home what was lost in the institutionalization and “brahminization” of Bharatanatyam and how the reformist zeal for sanitization removed the sensual core of bharatam.

In her Sangita Kalanidhi speech, Balasarawati subtly drove him the point that core aspects of Bharatanatyam had been lost

In an interview to me for an article in The Times of India, Douglas Knight, her son-in-law, said, for Bala, Shringara was never separate from Bhakti. And for all the masters of art going back to hundreds, if not thousands, of years, they were not separate, he said. Today’s Bharatanatyam, highly choreographed and preset as it is, has separated the two and almost made the former invisible, he said.

Krishna’s speech at Music Academy will be landmark. He is extremely articulate and never minces his words. What will be interesting to watch though, six months after the election results, will be his focus. Knowing his cleverness with words, he would probably point to larger issues while talking about his own formative influences. He will certainly reiterate that the emperor still has no clothes.

Personal resonance

The views of T M Krishna Krishna resonated with me very early. I had come back after ten years to India and that stint abroad had instilled some distance and objectivity in me. Among the things we take for granted in Tamil Nadu is that the Carnatic concert music scene is ruled by brahmins and it is their exclusive preserve. I was just struck by why this was taken for granted when it went against all norms of inclusiveness that a modern society should uphold.

In December of 2011, a few months after the start of Pudhiya Thalaimurai, I made a series on Carnatic music coinciding with the Margazhi festival for the channel. Isai Sangamam ran every day for two weeks in the morning.

The decisionmakers were skeptical that it would succeed. They felt the overwhelming majority of viewers who were not brahmins would not relate to it.

But the series proved them wrong. We started out with 26 minutes of programming for the half-hour slot – four minutes were for ads. By the last day, we were down to 21 minutes – nine minutes of ads. Ads are driven by ratings.

As a visual medium, television focuses almost fully on looks. I was keen that even if the performers looked brahmin and spoke brahminical Tamil, none of the panelists should. I chose the panelists through pure racial profiling. The anchor, the expert and the musician should not be fair skinned and should not speak brahmin Tamil. Those two checkboxes had to be ticked so visually there was no disconnect.

One can recall Balasaraswati’s 1973 speech that, in and of itself, seemed typical. But, just by recounting her formative years and her influences, she subtly drove home what was lost in the institutionalization and “brahminization” of Bharatanatyam and how the reformist zeal for sanitization removed the sensual core of bharatam

The last day’s theme of Isai Sangamam was why non-brahmins largely kept away from the concert performance scene. A healthy, no holds barred discussion brought the series to a close.

So when Krishna spoke up, I was jubilant. I interviewed him and wrote a glowing review of A Southern Music in The Times of India.

So when Krishna spoke up, I was jubilant. I interviewed him and wrote a glowing review of A Southern Music in The Times of India.

What was striking in the book was Krishna’s method. He had studied in The School of the Krishnamurti Foundation of India and had imbibed the Jiddu Krishnamurti method of considering things.

Listening to JK’s speeches and reading his books need no previous knowledge. They do not refer to anything said or written before or outside. Culturally neutral, they do not claim to draw from any other source. They are constructed from first principles. The reader or the listener is often led through a journey of discovery that requires only rational thinking with no preconceptions nor knowledge. Krishna’s book constructed, presented and explained Carnatic music in a powerful way, warts and all.

A free forum

Soon, however, I presented counters to my own article including from Badri Seshadri in The Times of India. Sampath Kumar, former BBC correspondent and faculty at Asian College of Journalism, felt Ilayaraja was far more deserving of the Magsaysay award for his service to Carnatic music and taking it to the masses.

In inmathi.com too, I have attempted to present all narratives and arguments. Without much success, I have sought to present the BJP side of things.

Inmathi should be a free and open forum for all views. It has sought to bring together opinions and narratives of all hues, besides pure reportage, since truth always resides in the margins, the gray areas. The news media’s sacred duty is to present the truth, however it is.

What was striking in the book was Krishna’s method. He had studied in The School of the Krishnamurti Foundation of India and had imbibed the Jiddu Krishnamurti method of considering things.

In that breath, inmathi published Chitravina Ravikiran’s take on the MeToo movement. The allegations engulfed him too.

I nevertheless admire Ravikiran’s music, his extraordinary knowledge and repertoire, and readiness to share that vast knowledge. I, however, don’t agree that Krishna has polarized Carnatic music. The polarization has always been there.

To be fair, Ravikiran may be a fan of Narendra Modi today but he defended Carnatic music artists’ singing of Christian devotionals.

Brahmin peeve

Many brahmins say that, barring priesthood in temples, the sabha scene is their last remaining stronghold in the land of their birth. They tenaciously hold on to it and react viscerally if someone points out that this beautiful art form that is truly a treasure simply cannot sustain on such a narrow social base. Ranjani-Gayathri’s letter obviously comes from that space.

Their anger needs to be understood, too, especially their rather dismissive take on Periyar who is certainly not in the box they put him in. It would take scholarly analysis to see if the demeaning stereotype of the “loose” brahmin woman can be attributed to him even indirectly. But it’s common among Dravidianists.

Amidst the consistent promotion of progressive ideas in all spheres, did Dravidianism borrow from the race thinking prevalent across the world pre-World War II? It was common in that age to hold that people who are born in a race, ethnicity, caste group were fundamentally different. It’s a thinking that is promoted by bigots everywhere to this day. The Jew, the Muslim, the brahmin, the pariar – stereotypes of bigotry.

All these will not be resolved anytime soon. But they need to be aired and we must learn to listen to each other.

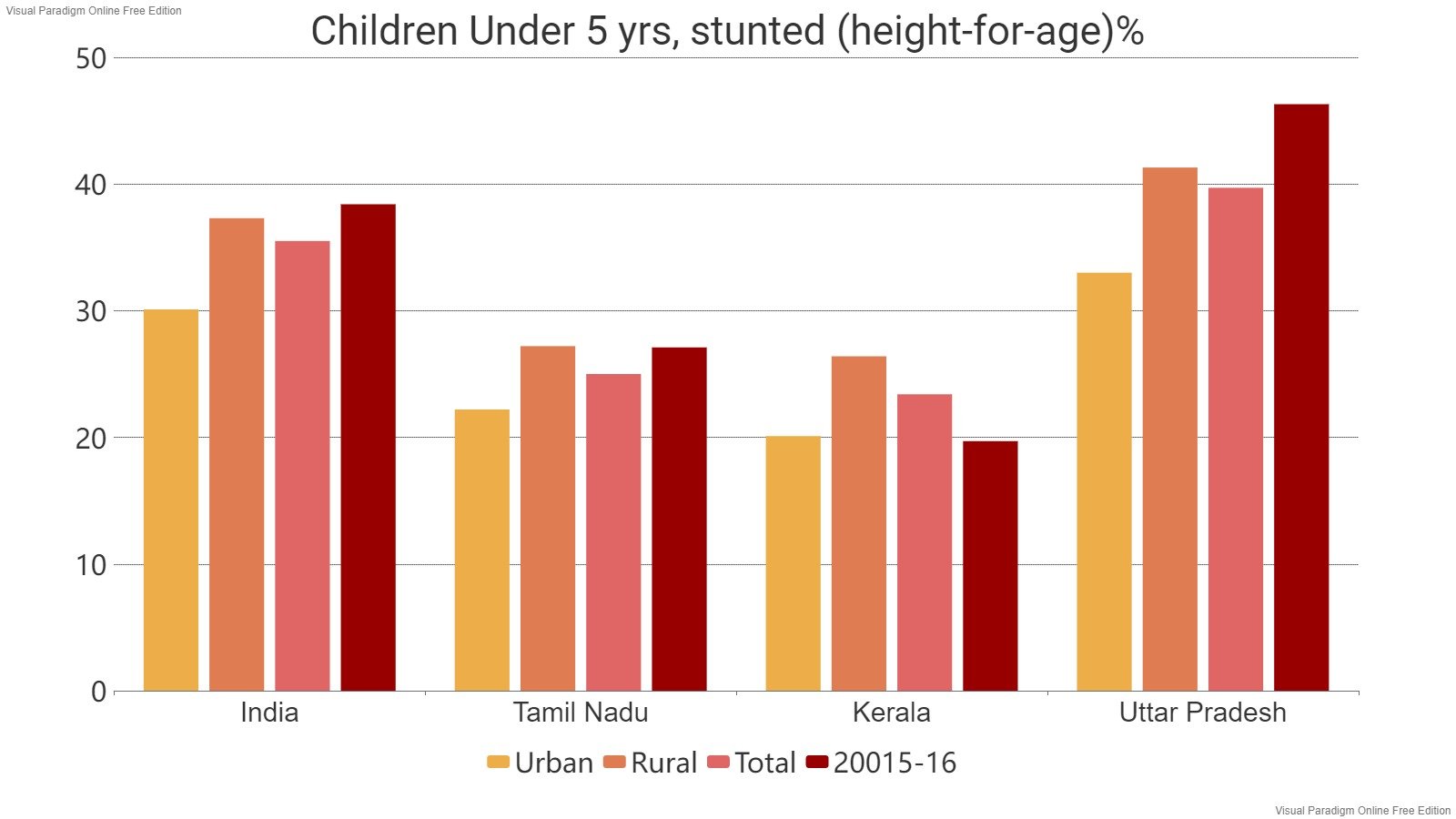

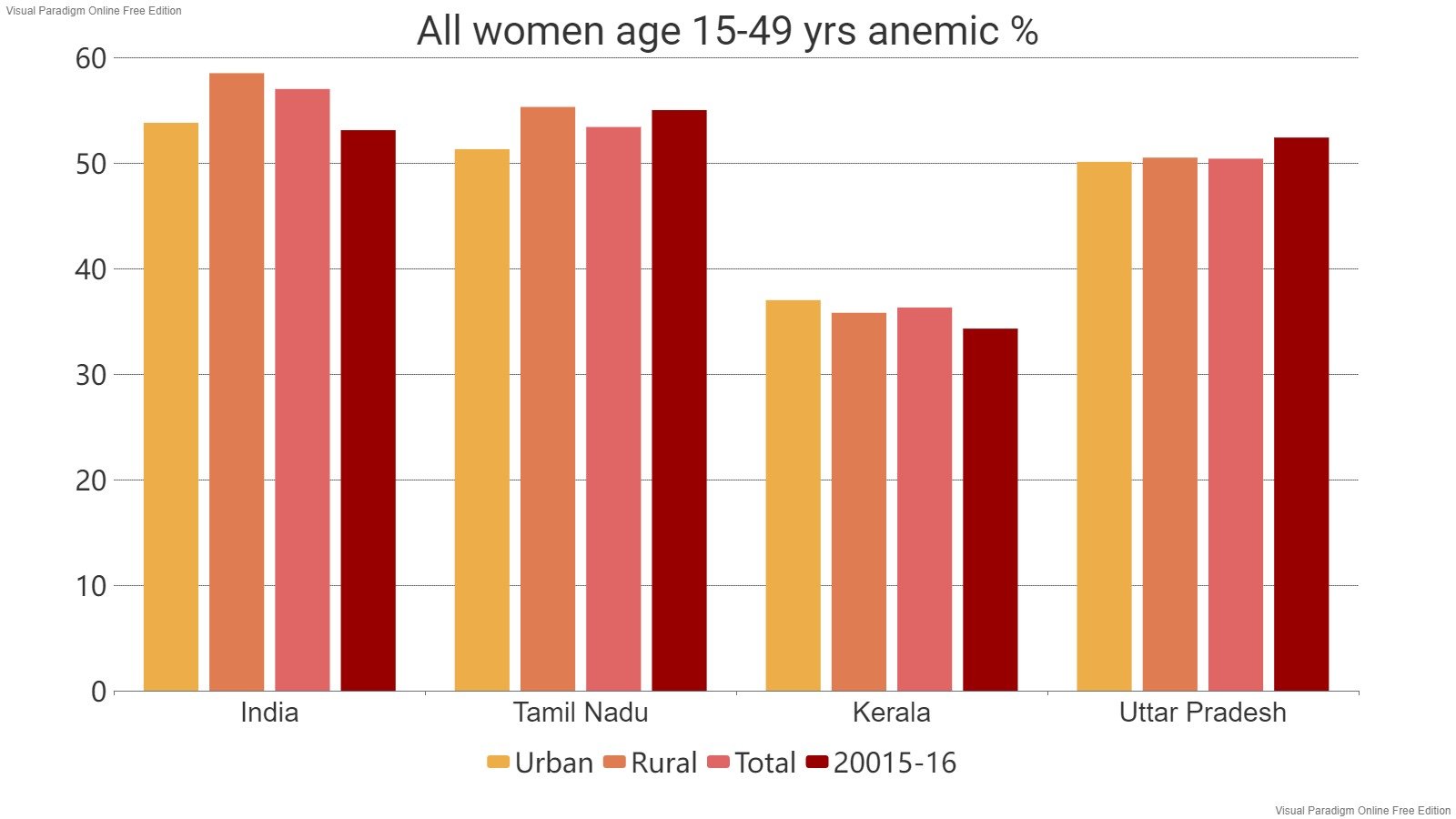

To conclude: Carnatic music is art music, as T M Krishna would say, and is therefore not for everybody. But the somebody who take to it should naturally be drawn from all sections.

Would Ilaiyaraja have become a vidwan if the concert performing scene in Carnatic music had been open and available to anyone who has the talent for it? Quite possibly. But the networks of patronage and broad social group thinking ensure that the milieu is forbidding for others though there is no formal entry barrier. That’s the ugly truth.

Listen to T M Krishna – for his singing and speaking.