Read in : தமிழ்

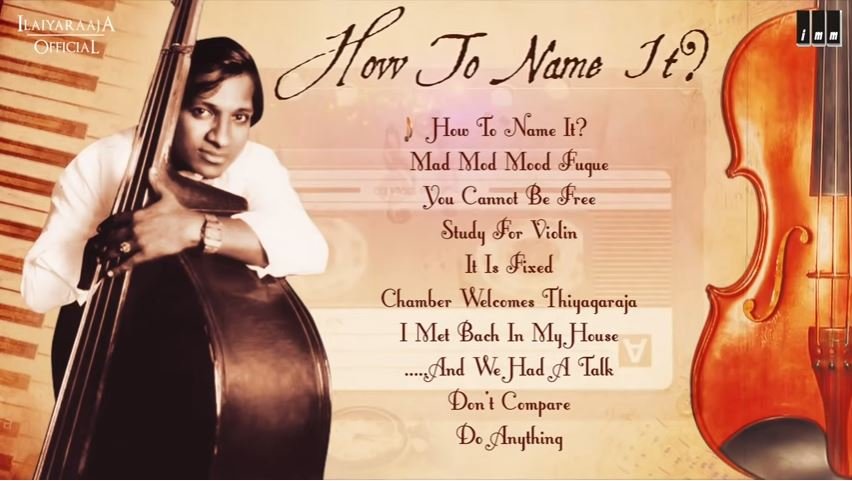

Sometimes, it takes much effort and skill to produce the simplest of things. Music is one. Ilayaraja’s music has that quality of simplicity. It breezes in through the ear and stays in our mind forever. And it takes genius to make it. The Album How To Name It was one such Ilayaraja musical product.

Today, such Carnatic-based fusion is common. Everyone and their pet are doing it on YouTube. Ilayaraja introduced the genre for the popular audience some 35 years ago.

So, when Ilayaraja announced there would be a How To Name It – Part 2, many were wondering what it would be like. The maestro’s musical journey in the intervening years has taken him to various musical places. Will Part 2 echo that evolution? Or will it break completely new ground? Or will it be a throwback to the early Ilayaraja.

Just like Rajinikanth, Ilayaraja was born in a corner of the world, went through an arduous, challenging journey before bursting on to the scene as a well-trained and honed artist. In his musical life, Ilayaraja has had many ups and downs. Each of the heights he touched and the experiences he acquired can fill any other human’s entire life.

At first self-taught, Ilayaraja learned Western and Carnatic music with their nuances formally. His first phase was with his brother, the bard of leftist ideology in Tamil Nadu, Pavalar Varadarajan. This started when he was 14 years old and involved helping his brother make rousing anthems heralding the coming revolution and melancholic numbers lamenting the fate of the oppressed.

At first self-taught, Ilayaraja learned Western and Carnatic music with their nuances formally. His first phase was with his brother, the bard of leftist ideology in Tamil Nadu, Pavalar Varadarajan. This started when he was 14 years old and involved helping his brother make rousing anthems heralding the coming revolution and melancholic numbers lamenting the fate of the oppressed.

The second phase started when he was 18 years old and he came seeking opportunities in the film industry to Chennai. Ilayaraja apprenticed with Salil Chowdhury, G Devarajan, Dakshinamurthy, MS Viswanathan, GK Venkatesh, V Kumar and others. He learned Western classical from Dhanraj Master and Carnatic from TV Gopalakrishnan.

Ilayaraja entered the third phase when he was 33 years old and scored music for Annakili. Film music gave him the platform to bring all his musical ideas that came from diverse sources to reality. It was where Ilayaraja’s musical worth was validated, successfully. How To Name It and its successor Nothing But Wind represent the apogee of the third phase in his musical journey.

Ilayaraja had started experimenting with film music at that time. Ullasa Paravaigal, Sigappu Rojakkal and Dharmayuddham gave him opportunities and the space to experiment. The phrases and the embellishments he introduced in the songs of the films were unique. The two albums, however, gave him an opportunity to express the ideas that could not fit into the framework of Tamil movies. While musicians such as L Shankar and L Subramanian or even Shakti were exploring fusion as high art, Ilayaraja presented it for the common people.

What was remarkable was that How To Name It was composed when Ilayaraja was at his busiest. He was scoring music for Tamil, Telugu, Kannada, Malayalam and Hindi films, which left him little time to explore and innovate. In the morning, he would compose songs for one film, afternoon recording for another movie, and evening he would be doing background score for yet another.

Today, composers take 10 to 15 days to make music for one reel. At that time, Ilayaraja would finish an entire film in three days. Yet, since movies can be limiting to his vast talents, Ilayaraja took time to make How To Name It.

Beyond money and fame, an artist needs self-satisfaction. The two albums gave Ilayaraja that.

How To Name It has become standard playing at cultural events across schools and colleges. Its freshness hasn’t dimmed over the three decades since its release. The 10 musical ideas were a tribute to Carnatic composer Thyagaraja and Western composer Bach. Do Nothing became the signature track of Balu Mahendra’s Veedu. A phrase that wasn’t included in the album became Valai Osai Gala Gala sung by Lata Mangeshkar. How To Name It put Ilayaraja in the league he rightfully belonged to.

Inexplicably, Ilayaraja started limiting himself in film music in the 1990s. He did not venture into Hindi film music and did not seek to make his presence felt there. He cut back on his experimentation in Tamil film music, and stuck to the requirements of the script and story. After he reached the top, there was little encouragement for him to go higher. Most filmmakers were content in having music that would make their film do good business. He was still doling out hits and the film audiences lapped them up. But Ilayaraja had a creative peak which turned out to be a block.

Inexplicably, Ilayaraja started limiting himself in film music in the 1990s. He did not venture into Hindi film music and did not seek to make his presence felt there. He cut back on his experimentation in Tamil film music, and stuck to the requirements of the script and story. After he reached the top, there was little encouragement for him to go higher.

In the 2000s, the songs started to lose their shelf lives such as in Kadhal Kavidhai, Time, Hey Ram and Sethu. Ilayaraja’s genius was getting absorbed in spirituality, Tamil poetry, photography and so on. For that reason, it seemed How To Name It would be a one-off creation.

The background music he scored in Mishkin’s Onayum Attukuttiyum and Suseendran’s Azhagarsamiyin Kudhirai were grand but didn’t stay in the mind. Compared to the natural exuberance and experimentation in the 1980s films, these looked strained, even artificial. A made for Ilayaraja film like Kadaisi Vivasayi was not to be his.

Ilayaraja seems to have hit a low in his musical journey, finally. At this time, he has announced that How To Name It Part 2 will be out soon.

The energy he had in the 1980s for new elements is not there anymore in him. He is standing on the top of the hill and doesn’t need to fly towards the sky. But he seems to want to do exactly that, prove himself.

Part 1 fused Carnatic and Western. Perhaps there is an unexplored territory for him in Part 2. But it’s one he is absolutely familiar with, even born into. What if he fused the folk music of his roots with other genres and presented it to the world, not just Tamil Nadu? How would that be?

What if Pannaipuram met Vienna through Mayamalavagowla? Intriguing indeed for even Ilayaraja.

Read in : தமிழ்