Read in : தமிழ்

Have you heard of this curious pre-wedding custom in parts of Tamil Nadu where the bride’s male cousin has a mock argument with the groom? It was recorded as far back as 1917 by British ICS official H R Pate who compiled the Tinnevelly District Gazette for the Madras District Gazetteers.

One of the groups that practice this custom is the ‘parathava’ community of Catholic fishermen in Thoothukudi. Called ‘vasapadi mariyal’, which roughly translates to blocking the way to the door step, the custom is a nod to the formerly common practice of marriage between cousins.

The muraimappillai (a male first cousin) makes a show of objecting to the groom’s attempt to marry the woman who according to former norms would have been his bride. He blocks the way of the groom and prevents him from entering her home. The groom and the first cousin then indulge in a mock argument rendered in the form of songs, after which the groom would pacify the muraimappillai with gifts of gold or money to allow him to marry the bride.

The British official Pate even translated these quirky songs sung during the ceremony into English.

Folklorist Prof A Sivasubramanian says the ritual evolved after the community began to leave behind the practice of consanguineous marriages (usually unions between first cousins).

Among the South Indian states, Tamil Nadu tops in β-thalassemia with a frequency rate of 4%. Children suffering with this autosomal disease require frequent blood transfusion and iron-chelation treatment.

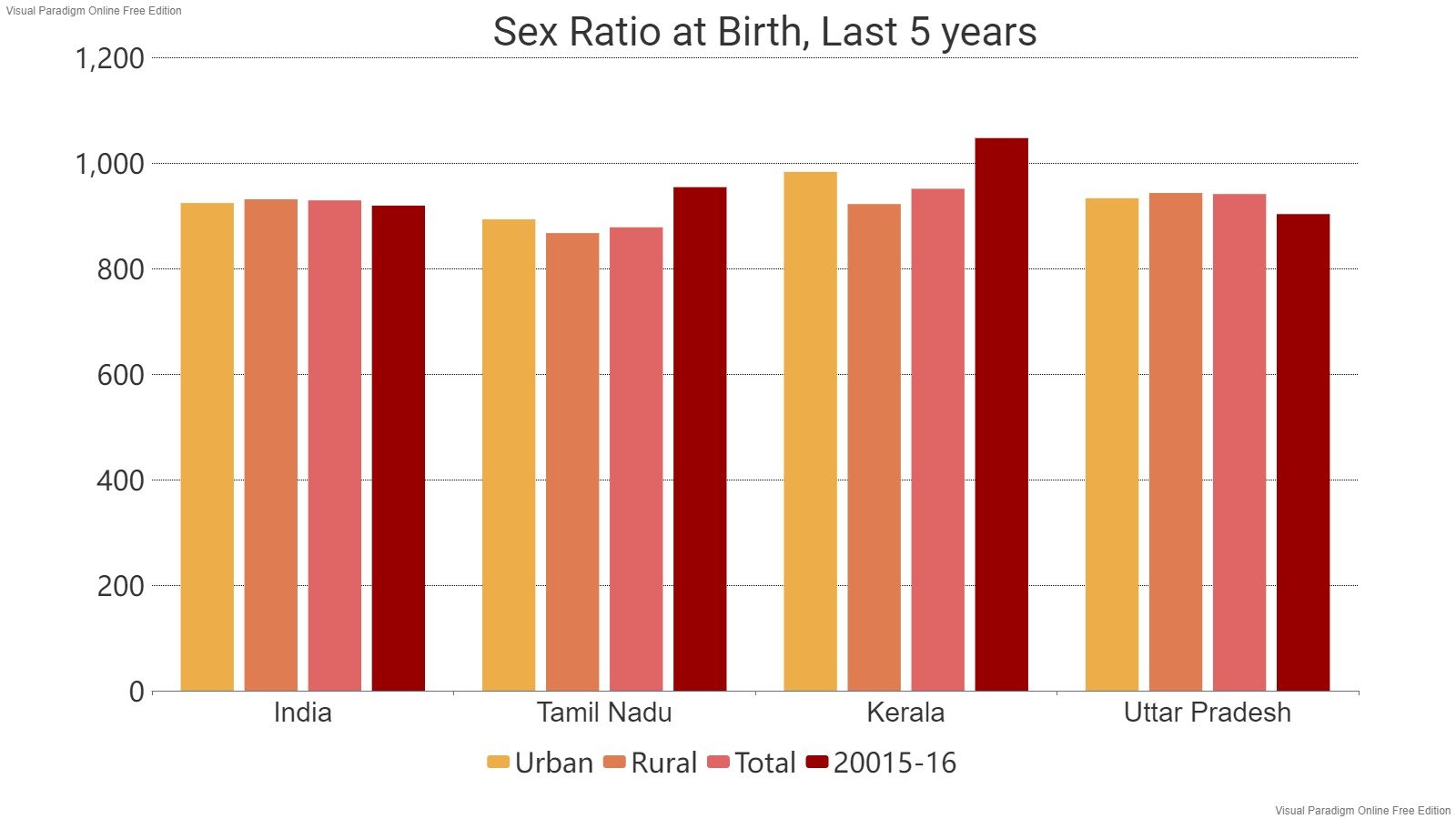

However, endogamy is older than caste and marriage between cousins is still quite common, say experts, as such unions ensure that property stays within the family. Child marriage and sati were also tools that were used to ensure that the control of assets remained in the family, says Sivasubramanian. But the health risks to children born of marriages between cousins far outweigh any perceived socio-economic benefits.

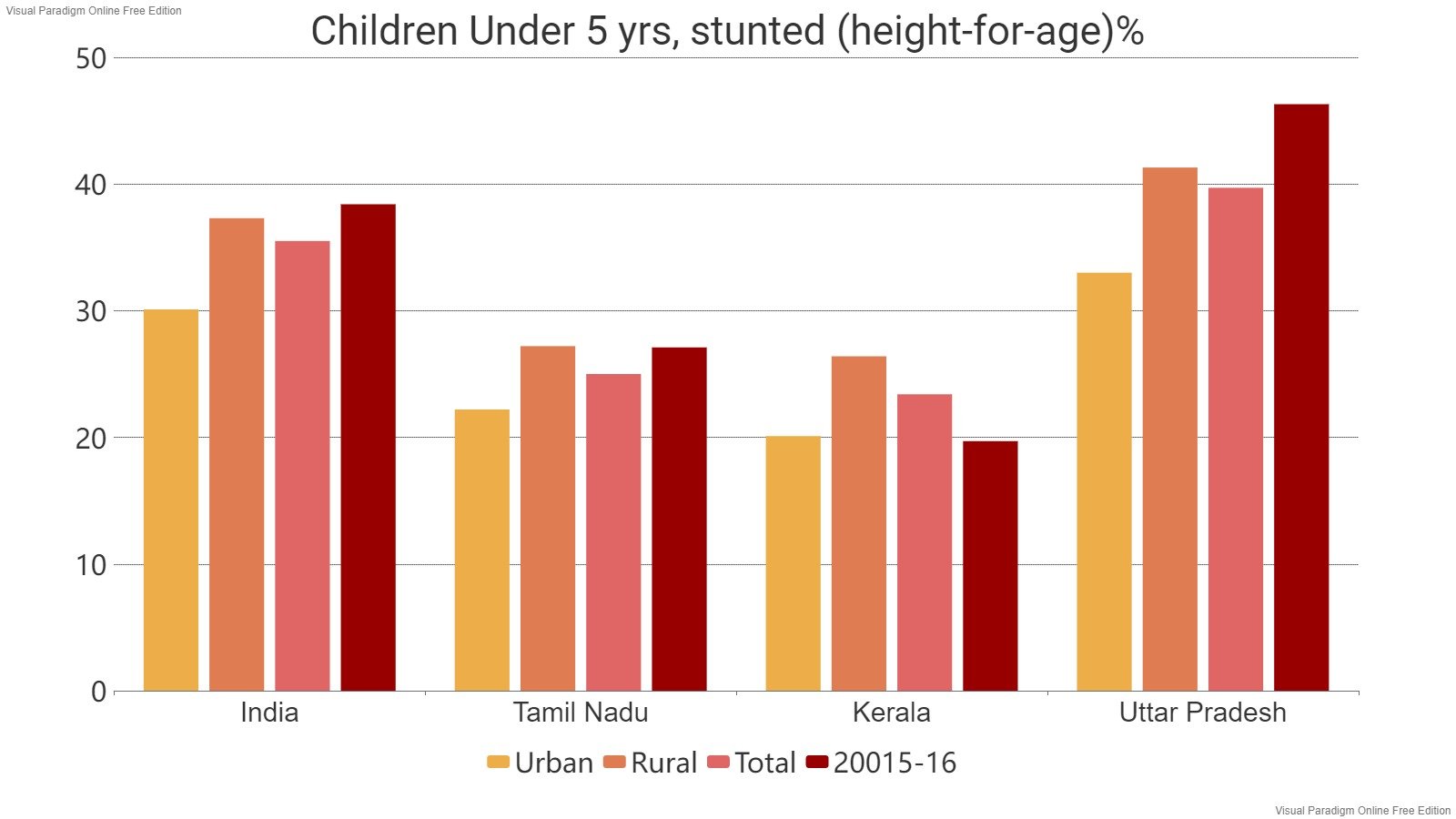

Researchers say inbreeding has caused genetic anomalies among Tamils. Yet, marriage between cousins continues to be quite common. Among the South Indian states, Tamil Nadu tops in β-thalassemia with a frequency rate of 4%. Children suffering with this autosomal disease require frequent blood transfusion and iron-chelation treatment.

Another genetic disorder affecting Tamils is hemophilia, a disorder in which blood doesn’t clot. The tribal communities in Tamil Nadu have sickle cell anemia, a genetic defect commonly found among people of the Black race. The closely-knit tribal communities don’t find matches beyond their groups and the consanguineous marriages keep the disease alive. Intriguingly, this anomaly shields them from malaria just like Africans have immunity towards this vector-borne disease, say researchers.

The incidents of muscular dystrophy, autism and down syndrome are also high among Tamil people, says Prof A K Munirajan, Head of Genetics Department and Director of Dr ALM PG Institute of Basic Medical Sciences at Madras University.

The research paper ‘Castes, Migration, Immunogenetics and Infectious Diseases in South India’ by R M Pitchappan from Madurai Kamaraj University’s Department of Immunology studied three population groups within a 70-kilometer radius of Madurai. The study finds that Piranmalai Kallars and Sourashtrians are susceptible to sputum positive tuberculosis while the Vellalar community is susceptible to psoriasis.

In our last article What Population Genetics says about Tamils, the allergic reaction of Arya Vaisya Chettys to the anesthetic drug scoline was discussed. A genetic defect prevents their bodies from metabolizing the anesthetic drug. In the same way, these three communities have the genetic defect that prevents their bodies from producing immunology response to the specific diseases. “It is not a disease but a gene defect,” says Munirajan.

Like Arya Vaisya Chettys, Piranmalai Kallars commonly practice consanguineous marriages. Maternal uncles or their sons have the right to claim the hand of the bride. Sourashtrians, who migrated from Gujarat and settled down in various parts of Tamil Nadu, also follow the custom. The Vellalar community is no different. “I have seen ugly family feuds when the groom or bride was not selected from among first cousins,” says Sivasubramanian.

There are however some permutations and combinations that are a no-go area among some communities however. For example, till some decades ago, Tirunelveli Nadars wouldn’t get into matrimonial relationships with their counterparts in Kanyakumari. Similarly, the Arunattu nadars (nadars in Virudhunagar district) and the Therinadu (Theri Kaadu in Tiruchendur region) nadars.

A research paper ‘Castes, Migration, Immunogenetics and Infectious Diseases in South India’ by R M Pitchappan from Madurai Kamaraj finds that Piranmalai Kallars and Sourashtrians are susceptible to sputum positive tuberculosis while the Vellalar community is susceptible to psoriasis.

The vellalar community living in Karisal region (black soil region of Thoothukudi district) also stayed away from marriage with the Vellalar community in Thamirabarani river belt. Though they belong to the same community, the endogamy remained within the same geography. They had apprehensions and prejudices about members of their own community if they lived in a different region. So, they preferred consanguineous marriages within the same village, town or district.

“Ultimately, the consanguineous marriages helped them to stay put in their own localities and prevent wealth from moving from one place to another,” says Sivasubramanian.

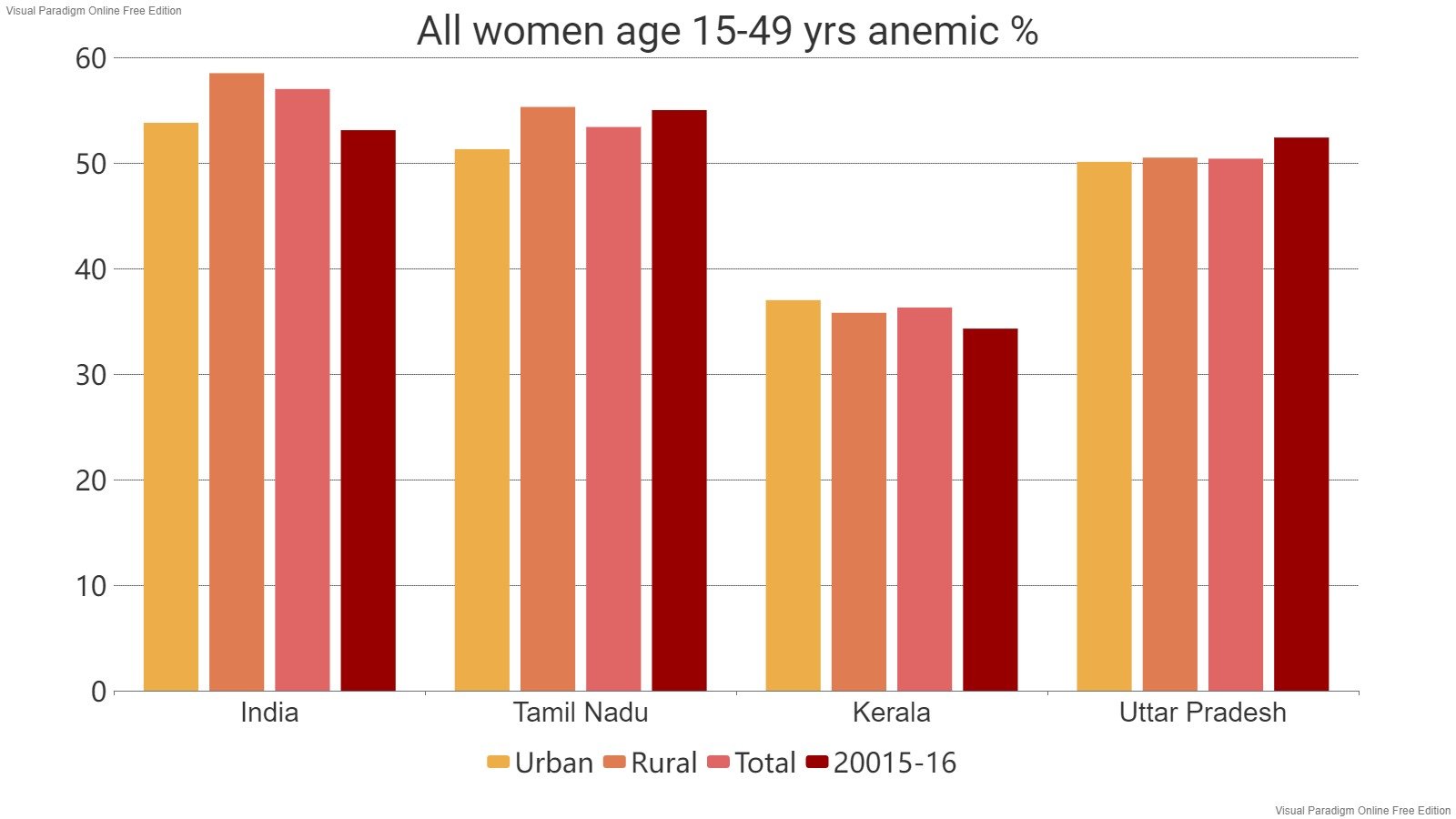

Genetic diseases are becoming a burden, says Munirajan. A family undergoes tremendous pressure mentally and financially when a child suffers from thalassemia, autism, down syndrome or muscular dystrophy. The dominant gene however defect doesn’t pass on to the next generation but this is simply an unhappy consequence, as the affected persons don’t live long enough to reproduce.

The problem is the recessive gene defects carried by healthy people. When both parents have this recessive defect, the probability of it becoming the dominant defect in children is 50 %. “The communities still bet on this probability for socio-economic reasons, rather than avoiding consanguineous marriages,” says Munirajan.

After Thalassemia became a disease burden, it was included in the National Health Mission. Awareness drives were conducted among communities to avoid marriages among close relatives. But where such marriages had already taken place, the couples could be given genetic counseling.

The fetus could be screened in the first trimester for genetic defects. If defects are found, the pregnancy could be terminated. But the tests, each costing Rs 10,000 or more, are expensive. “Counseling could be given free of cost but poor families won’t go for the costly testing. This is a serious challenge,” Munirajan says.

A more reasonable solution for the problem is sensitizing communities about the genetic diseases and defects that consanguineous marriages could cause. Promoting marriages among distant relatives could be a saner option considering the cultural implications in our country, experts say.

Read in : தமிழ்