Read in : தமிழ்

Another edition of the Swachh Survekshan awards and honours was rolled out recently for 2022, hiding basic failures in India’s urban waste management as envisaged under law. Going by the metrics of the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs, Tamil Nadu fared badly, with only one award for Innovation and Best Practices going to Podanur, a small suburb of Coimbatore.

The results were better in the rural category for Tamil Nadu on high efficiency of water supply through household connections.

The Swachh Survekshan urban awards and marks are obviously influenced by perceptions rather than by successes in moving waste management to a circular economy — one where materials are recovered from the waste of cities. This approach is envisaged in the Solid Waste Management (SWM) Rules.

Pollution burden

Data on municipal solid waste — published not by the Housing Ministry, but the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) — bear this out. Further evidence is available from the Ministry of Jal Shakti’s Central Monitoring Committee on gross inadequacies persisting in some States in complying with the MSW Rules, 2016, and Plastic Waste Management Rules, 2016.

Tamil Nadu, as one of India’s most urbanised States, contributes about 10-12% of the country’s GDP, and tips the solid waste burden scale at 13,422 tonnes generated per day, of which 95% is claimed to be collected, and 9,430 tonnes is treated. A further 2,301 tonnes per day is landfilled

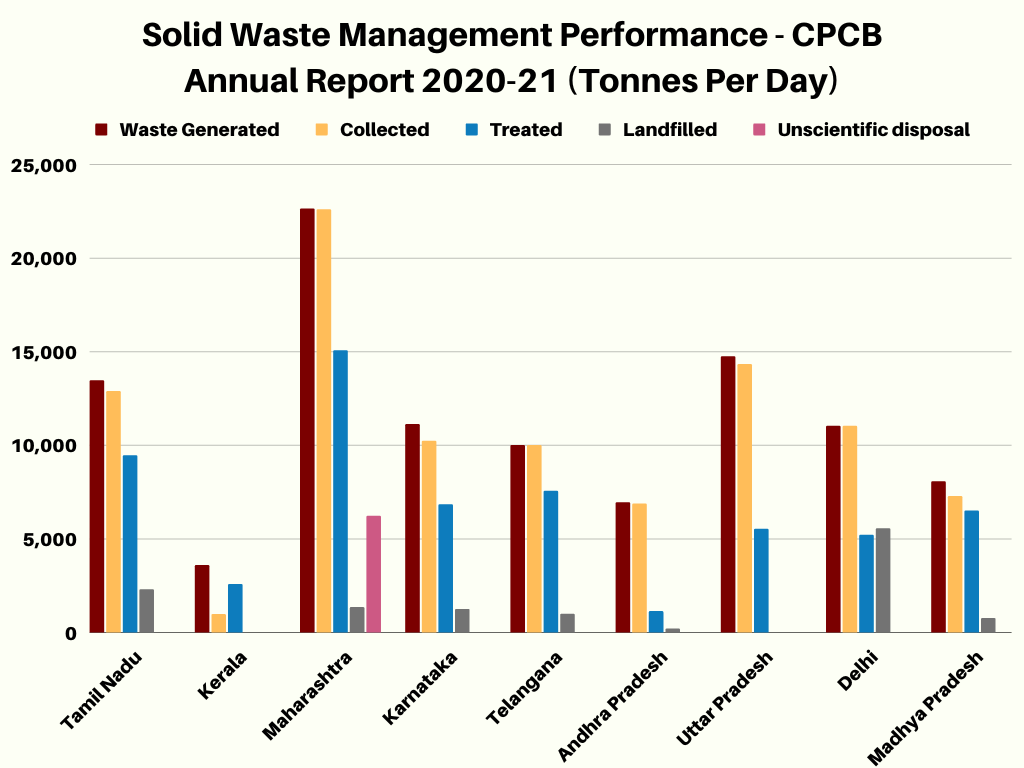

The latest data published by the CPCB for 2020-21 give an indication of the scale of the problem. Eight of the largest States besides Delhi together produce a total of 1.01 lakh tonnes of solid waste per day, of which nearly 96,000 tonnes is collected, just over 59,000 tonnes gets treated and 12,400 tonnes is sent to landfills. India generates 1.6 lakh tonnes of MSW in a day.

Tamil Nadu, as one of India’s most urbanised States, contributes about 10-12% of the country’s GDP, and tips the solid waste burden scale at 13,422 tonnes generated per day, of which 95% is claimed to be collected, and 9,430 tonnes is treated. A further 2,301 tonnes per day is landfilled.

For comparison, Madhya Pradesh, in which the “cleanest” city in India, Indore, is located generates for the entire State, a total of 8,022 tonnes per day of waste. Indore had a population of 19.6 lakh in 2011. The claimed collection efficiency is 90% while the treatment level is 80%. Neighbouring Maharashtra, a State with a major industrial and economic base, has a staggering waste volume of 22,632 tonnes per day, and a claimed collection efficiency of 99%.

Also Read: Swachh survey: losing ground on construction waste

Lost perception battle

Once again, Tamil Nadu has lost the perception battle, in spite of contracting with private firm Urbaser Sumeet in Chennai to manage the capital’s solid waste. This is being blamed by the civic agencies on public non-cooperation. In the existing scheme, the key factor for cities and States aspiring for Swachh honours is not a strong process, but a visibly clean outcome matching the age-old dictum of “out of sight, out of mind.” There is strong pressure to incinerate the city’s waste, a controversial method because of real pollution concerns.

Take the key criteria for a Swachh winner:

- Segregated waste collection

- Cleanliness of roads, public toilets

- City beautification

- Cleanliness of market areas, residential areas, drains, water bodies

- Daily sweeping in residential areas

- No open garbage dump

- Grievance Redress system

There are other factors too, such as the effectiveness of the single-use plastic ban, innovation to reduce, reuse and recycle at the ward level, better working conditions for sanitary workers, benefits to informal waste workers, capacity building for local body staff, and augmenting physical infrastructure.

Evidently, applying these to a massive and sprawling city like Chennai, or even to smaller cities such as Coimbatore, Trichy and Madurai would not produce a high score, due to the lack of process improvements. The plastic ban is routinely flouted in Chennai.

Sustainability ignored

However, the Swachh Survekshan method itself fails the test of sustainability, since it has no core sustainability metric like negative pricing for management of waste. Negative pricing would make it incumbent for the SWM agency to reduce the volume of waste to be disposed of, much of the urban waste being segregated and materials recovered. Neither is the Survekshan method outcome-based, measured in terms of actual materials recovered, including precious materials.

In the existing scheme, the key factor for cities and States aspiring for Swachh honours is not a strong process, but a visibly clean outcome matching the age-old dictum of “out of sight, out of mind.” There is strong pressure to incinerate the city’s waste, a controversial method because of real pollution concerns

In Chennai, and Tamil Nadu in general, there is no clarity on compost volumes generated from municipal waste. It is widely recognised that the dominant fraction of Indian MSW is organic waste. The Swachh Survekshan toolkit for 2022 lists circularity of wet waste processing as worth 150 marks. In the case of dry waste, the award system accounts for 100 points, and includes materials that may be sold after recovery. In Chennai, Urbaser Sumeet personnel often sell recovered recyclable materials to local scrap dealers, and there is no audit.

Deeper problems confront Tamil Nadu on solid waste management and sanitation. The Central Monitoring Committee’s 12th meeting held on February 4, 2022 noted that there is a gap in the treatment capacity for sewage of the order of 1,359 million litres per day, which would go down only partly to 1,000 MLD with the completion of new and proposed treatment plants.

Also Read: The story behind Tamil Nadu’s poor showing in Swachh rankings

The marginally updated figure for MSW in the State filed at this meeting shows a total waste volume of 14,292 tonnes per day, with a treatment efficiency of 68%. Tamil Nadu promised to file an updated report through a professional agency on its waste management, sanitation and coastal monitoring efforts in four to five months from February. The meeting held by the Jal Shakti Ministry noted tardy efforts in the State, especially on starting new Faecal Sludge Treatment Plants (FSTP) to handle rural sewage gathering in tanks, besides coastal pollution management planning. “Compliance status of the 36 common effluent treatment plants (CETP) is not provided,” the meeting minutes show.

The Chennai Rivers Restoration Trust (CRRT), headed by the Chief Secretary, was highlighted as a major initiative, with fresh sanction of Rs.2,400 crore for restoration of the Adyar, Buckingham Canal and Cooum rivers, indicating a fresh cycle of public expenditure on an issue that has consumed much funding in the past with almost no visible outcomes.

Even if it were to ignore the quest for Swachh awards (Kerala too got no awards for urban local bodies), Tamil Nadu can raise its environmental metrics. Urban waste management is the easiest part of the puzzle, requiring a partnership with citizens in which they are directly incentivised to segregate and dispose their waste.

Read in : தமிழ்