Read in : தமிழ்

The Tamil word ‘paran’ is one of several words that have been knocked out of existence in the language. Part of old-timers’ lingo, paran meant attic or loft. It was an indispensable feature of houses built in those days, mostly in villages, where all things dispensed with or condemned were dumped. So, quite naturally over the years, paran became a synonym for archival space.

The paran was home to old bottles, vessels gifted to grand-daughters for wedding by grandmas and great-grandmas, easy-chairs that used to keep the grandfathers who were mostly couch potatoes in the twilight of their life, three-legged chairs bereaved of one leg, a wedding blanket in tatters, walking sticks that walked no longer, jugs in which pickles were replaced with cobwebs, moth-eaten post-card and inland letters…

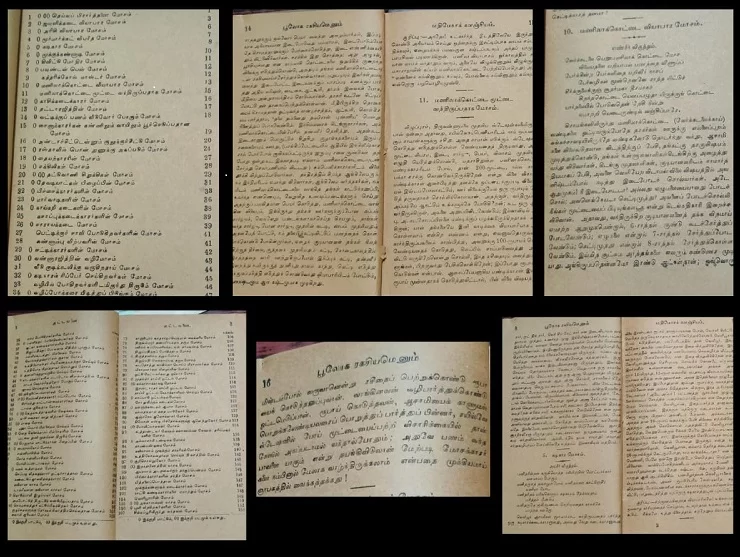

In a moment of pure serendipity, the paran in my house threw up a book from a trunk box of grandfathers’ times. The book was dog-eared and silverfish-eaten. It managed to show up, tumbling from a pile of books predating 1950 – a pile that is a hunting forest of moths and other insects.

This column will bring a few books of antiquity to light. An intro about the book and some excerpts will make up this column.

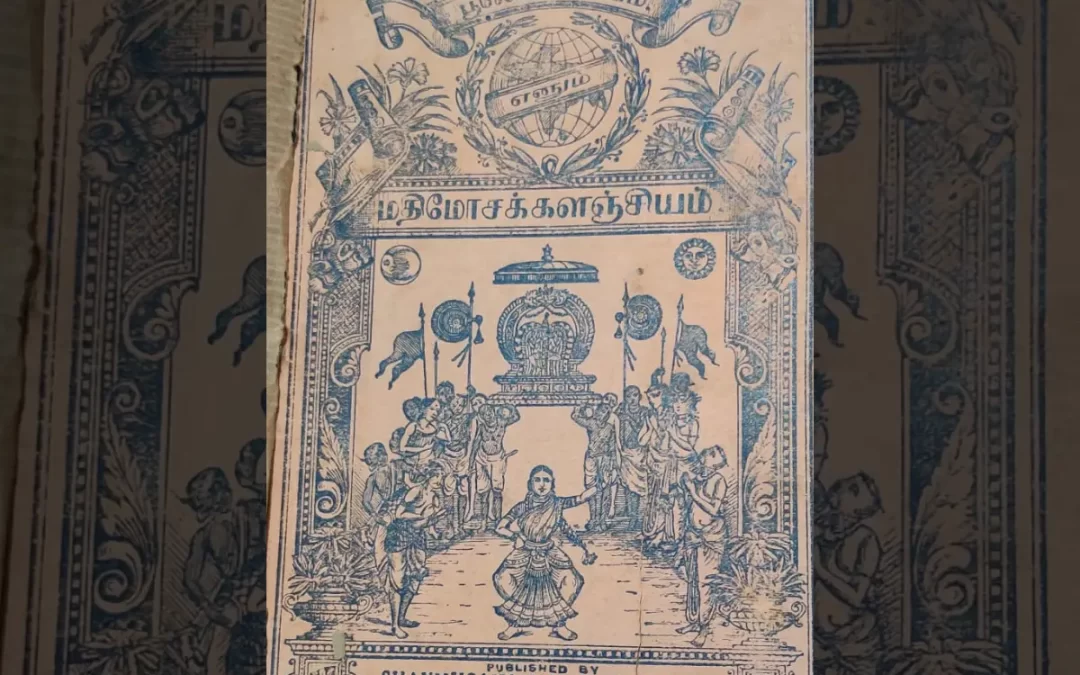

To begin with, now a rewind to the book Bhoologa Rahasiyam enum Mathimosak Kalanjiyam (encyclopedia on conning, aka earthly secret).

Heard about Tamil word ‘piththalai maathu’ (roughly, exchange of brass in English)? If you say yes, you must be more than 70 years of age.

The paran was home to old bottles, vessels gifted to grand-daughters for wedding by grandmas and great-grandmas, easy-chairs that used to keep the grandfathers who were mostly couch potatoes in the twilight of their life, moth-eaten post-card and inland letters…

This very old expression connoting fraud and conning was a buzzword in George Town, Broadway bus-stand, Moore Market and Central railway station in Chennai of the 1950s-60s. This was one of the cunning techniques adopted by conmen who were on the prowl for the gullible and the credulous. You would be taken for a ride; fooled into paying for what looked like gold and finally fobbed off with brass of little value. This was what was called brass exchange. You were conned into paying a lot of money for worthless stuff. Over the years, the expression became a byword for all fraud, not just the brassy ones.

In most cases, it was the innocent Andhra people more than the locals, who would fall prey to the cheats who could easily see through the innocence writ large on the faces of the prospective losers. The Telugu-speaking people, who would visit Tirupathi for temple worship, used to take a detour to have darshan of yet another god of theirs then living in the city – N T Rama Rao.

The opening sequence of NTR in a movie were often greeted by devotion. Telugus would light camphor and take it around like they would worship deities in temples.

Also Read: Dead End – where dead men do tell tales

It was easy to mark out the Andhra folks. Their shaven heads smeared with sandalpaste were a giveaway. Gullible, they were easy prey for tricksters.

The modus operandi of the deceivers was quite simple and irresistibly charming. A group of conmen would mingle with a cluster of Telugu bus passengers, speaking in Vijayawada Telugu. While one of the conmen would engage with the most naive in the group in casual conversation, another would be walking ahead along with other people in the group. Suddenly the man walking in front would drop a small packet as if unknowingly and would disappear in an instant.

The remaining conman, staying back and talking to the passengers, would run ahead in a knee-jerk reaction and take the fallen packet. While all others watched curiously, he would open the packet and from a pink tissue paper conjure up what looked like a gold chain glistening in the sunlight. To tap into the innocents’ godly feelings of devotion, the crafty man would prominently show a pendant engraved with the image of Lord Venkateshwara along with a bill showing the figure of Rs.5,000. Then, he would make someone in the group read the bill and know the fabulous price (in those days) of the chain.

The conman’s histrionic skill would convince the Andhra folk he was in trouble and deserved a helping hand. The women in the group would, a few steps away, go into a huddle and mobilize funds. Then the deal would be clinched after which the conman would vanish, enjoying a windfall

The credulous people would lap it up. Greed buried in them would surface and they would wonder aloud, saying, “O my! How unlucky he’s! He has missed a ten-sovereign chain.” They would feel as if luck was knocking on their door.

The conman would start using his gift of the gab and launch a short monologue thus: “How lucky I’m in these days when gold is quite precious and rare. But the catch is I need liquid cash quite urgently. If I am selling it, I will be booked on suspicion. So, if I get a buyer instantly, I’m ready to part with it even at half the rate.”

At that moment, the conman would strike the credulous people as a pitiable man deserving a helping hand. The women in the group would, a few steps away, go into a huddle and mobilize funds. Then the deal would be clinched after which the conman would vanish, enjoying a windfall.

Also Read: Salman Rushdie and the story of India

The encyclopedia is a compilation of many other cautionary tales. The Moore Market of yesteryear was clearly the conman’s haunt. It was his den.

If you asked the price of a bottled drink, the vendor would say, “25 paise.” After you were done with drinking, you would give him 25 paise. But the vendor, with a mighty menacing expression on the face, would snarl and say: “I said one rupee and 25 paise.” The thirsty customer had to cough up Rs 1.25.

It appears the writer of the book was a frequent fall guy at Moore Market. Conmen would often take him for a ride, it seems. And he sat down to write this book so others would be forewarned.

Read in : தமிழ்