Read in : தமிழ்

India celebrated its 75th Independence Day only on Monday, but an event in a western suburb of Chennai three days earlier is potentially the harbinger of change in perceptions around Indian Railways, on what the country’s manufacturing industry can achieve and how the much reviled public sector can deliver and stay alive in the face of impending privatization. On August 12, the third rake of India’s first train-set, the indigenously manufactured Train-18, was flagged off by Union Railway Minister Ashwini Vaishnaw at the Integral Coach Factory (ICF) in Perambur, Chennai.

Built using around 80% Indian components and without any Transfer of Technology (ToT) from foreign countries, the fastest train in the country ( with a top speed of 180 kmph) is envisaged to compete against high-speed trains from the developed world and is billed as a breakthrough in terms of incorporation of advanced amenities and technology in India’s rickety railway ecosystem. Mr. Vaishnaw announced that 475 more such rakes will be manufactured in the four years.

The Train-18 is a jewel in the crown of the ICF, the largest rail coach manufacturer in India officially claiming a turnover higher than China’s largest such unit. The factory has always been a silent workhorse, churning out close to 4,000 coaches every year with variants catering to long-distance trains, suburban travel in India’s metros and coaches for Sri Lanka and Bangladesh.

Though the speedster Train-18 took just 18 months from the drawing board to factory roll-out and has been running without any glitches since then, it had to face an enforced hiatus of three years between the manufacture of the second and third rake.

The ‘enforced hiatus’ was not because of COVID-19; and indeed encapsulates a potboiler of its own — but more on that later!

The Train-18 is a jewel in the crown of the ICF, the largest rail coach manufacturer in India officially claiming a turnover higher than China’s largest such unit

Meanwhile, Train-18, operated as India’s fastest train — the Vande Bharat Express between New Delhi and Varanasi, and New Delhi and Katra — has been celebrated rightfully as one of the few achievements of the current BJP government’s flagship ‘Make in India’ project.

Very Indian obstacles

In many ways, the train symbolizes the grit and tenacity of Indian engineers and managers and what they can achieve given the right leadership and environment. The experience of ICF and Train-18, however, suggests that the toughest challenge to ‘Make in India’ might not be lack of knowledge, skill or exposure to global competition, but quintessentially Indian issues like sloth, indecisiveness and the notorious ‘crab mentality’ in the Indian bureaucracy.

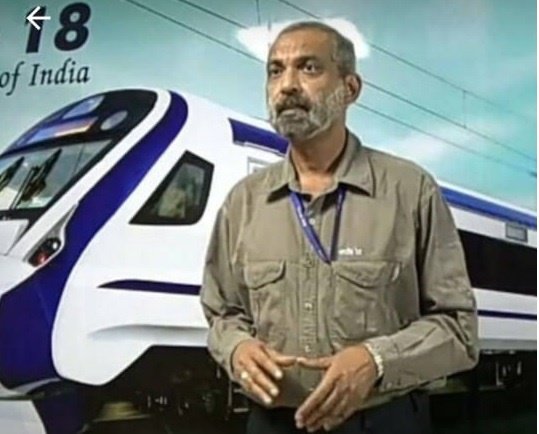

All these were encountered by the ICF team, as is detailed in the book My Train-18 Story by Sudhanshu Mani, ICF’s former General Manager under whose leadership the train was conceived and delivered.

In the book, Mr. Mani puts Train-18’s engineers on the same pedestal as the scientists of the much-feted Indian Space Research Organization (ISRO), although unseen and unrecognized.

Given the circumstances, the comparison is apt. ISRO is the envy of the world with its successful rocket launches at a fraction of the cost of foreign counterparts. Likewise, Train-18 was built in 18 months from design to commissioning at less than Rs.100 crore, which according to Mr. Mani is twice as fast and half as cheap as an imported train set. And this was done without compromising on the vision to provide globally competitive amenities and technology like vaccum toilets, wide gangways, underslung equipment, dispersed lighting and aircraft like seats whilst keeping the technology and manufacture indigenous.

During its test runs prior to launch, Train-18 comfortably breached the 180 kmph, though it is still run at 130 kmph due to restrictions imposed by the track infrastructure. Despite this, it still speeds up travel time between New Delhi and Varanasi by three hours as compared to the erstwhile fastest, the Rajdhani Express.

Also Read:

Budget announces 400 Vande Bharat trains in three years: Can ICF do it?

Bringing Bengaluru Metro to Tamil Nadu a win-win for both states

Along with the story of the technological breakthroughs, My Train-18 Story also recounts how each step of the train’s 18-month gestation was fraught with bureaucratic quagmires, incessant negativity, indecisiveness and inter-departmental rivalries that plague India’s railway bureaucracy. Mr. Mani links the crippling indecisiveness to the fear of vigilance action; even those who want to innovate fear being victimized given the complex tendering system.

Sample these: despite a general consensus on the necessity to upgrade coach design in India, Mr. Mani had to literally prostrate before senior officers to get the project sanctioned. During later stages, when the manufactured train was on trial runs, attempts were made by top railway officials to scuttle it by creating artificial roadblocks. Canards were spread about how the electricity drawn by the train from overhead electric lines could cause fires! Top newspapers even splashed fake photographs of fires beside the train a few days before it was launched to the public.

Sudhanshu Mani retired as the general manager of Integral Coach Factory and led the team which designed and developed the first two rakes of Train-18. Apart from My Train-18 Story, Mani has authored books on art, environment and his experiences in Indian Railways.

The final (albeit temporary) nail in the project’s coffin was when the officers of the core group, including Mr. Mani, were accused of tender malfeasance and slapped with vigilance cases. While exonerated later, the accusations cost some of these cutting-edge officers crucial promotion benefits, leaving a bitter taste.

Process is the punishment

The underlying feeling one gets through the book is that the managers of the project were able to resolve complex engineering and procurement issues more easily than the Machiavellian games played by the bureaucracy. This exemplifies how innovation in Indian manufacturing, especially in the public sector, is less about competing with the best in the world and more about navigating through suspicions of intent and deliberately labyrinthine rules and regulations.

Impediments to innovation in the public sector come not only from the top; managers also have to contend with legacy issues of strong unions, rampant corruption in procurement, favouritism to sub-standard suppliers in tenders and a widespread inertia to provide better services to the public.

In the Train-18 context, Mr. Mani also sets out solutions to some of these endemic obstacles — a major part of his book is about the ‘HR’ initiatives under his leadership, which he says laid the foundation and energized the employees for the technological upgradation. For instance, the accepted norm in railway factories was that shop floor employees work only 3-4 hours a day and even run businesses outside. May 1, the international workers day, is an unofficial holiday. How ICF challenged these norms without spoiling industrial relations is a lesson in deft governance.

As for awarding contracts, Mr. Mani points out that officers are loathe to award tenders in case of single participants even if their abilities are proven. One of the reasons cited by Vigilance Department in the cases filed against the team was that some contracts were awarded to Indian firms in a similar manner, but it was not considered if such firms were indeed best suited to deliver. Conversely, the author expresses frustration with the ‘L1 syndrome’ where government agencies have to award tenders to the lowest bidders which might compromise quality.

Impediments to innovation in the public sector come not only from the top; managers also have to contend with legacy issues of strong unions, rampant corruption in procurement, favouritism to sub-standard suppliers in tenders and a widespread inertia to provide better services to the public

Mr. Mani also discusses how the tension between transparency vs delivery is an issue that Indian society is unwilling to debate. In the government set-up, many officers sacrifice decisiveness fearing threats or allegations of corruption, even in the absence of a shred of evidence. But Mani says that the government’s Public Procurement Policy and General Financial Rules do empower the executive to select the ideal contractors or suppliers without affecting transparency and delivery of intended results. “Should public scrutiny be limited to only showman transparency without any premium on attainment,’ is a poignant question Mani raises in the book. Whether this is an advice that will be implemented across the board is doubtful, given how closely government officials work with publicly elected officials and the impact that mere allegations of corruption or favoritism have on public opinion.

Mr. Mani deals with these nuances in a chapter titled ‘Transparency’ where he deals with ‘honesty’ among government officials in a very clinical and candid manner, giving real-life examples of tendering and transparency. Such instances are nothing new for anyone who’s lived in India and been exposed to government work. More so, if one is a contractor or supplier to government agencies.

However, the success of Train-18 shows that successful ‘Make in India’ projects are not a pipe dreams. To paraphrase Mr. Mani, India would remain an importer of technology or a leased manufacturing space if a leadership with a sense of purpose, resolve, empathy and pride is not allowed to emerge and sustained.

Read in : தமிழ்