Read in : தமிழ்

For former DMK president and Chief Minister M Karunanidhi, Kanyakumari presented a political problem that gave him an opportunity to indulge in his trademark alliterative Tamil. “Tirunelveli is our border and Kumari is trouble [Nellai engalakku ellai, kumari engalukku thollai],” he said. The district’s politics continues to be dominated by national parties and Dravidian parties have often fought unsuccessfully to gain dominance. In the past it was Congress, CPM and even Janata Dal, now the BJP has a significant presence here.

Not only in politics, in other areas too, Kanyakumari stands apart, such as in culture, traditions, and even food habits. Even physically, the district stands apart. When one drives down Tirunelveli, the perennially parched lands of Tamil Nadu suddenly take a lush green hue when one enters Kanyakumari. “Kanyakumari is fertile. It’s geography is a key reason for that,” says N T Dinakar, writer, and author.

He adds that Kanyakumari boasts of four of the five land forms talked about in Sangam literature – kurinji, mullai, neythal and marutham. It has mountainous lands, besides forests, farmlands as well as the coast. “This has shaped people’s lifestyle and food habits,” says S Lazarus, an environmentalist.

He adds that Kanyakumari boasts of four of the five land forms talked about in Sangam literature – kurinji, mullai, neythal and marutham. It has mountainous lands, besides forests, farmlands as well as the coast. “This has shaped people’s lifestyle and food habits,” says S Lazarus, an environmentalist.

On the west is the Arabian Sea, east is Bay of Bengal and towards the south is the Indian Ocean. The Western Ghats taper off into farmlands.

Elsewhere in Tamil Nadu, rains come mainly from northwest monsoon. Here, both the monsoons bring rains. For most part of the year, it is pleasant, and doesn’t get too hot. Expansive farms and orchards dot the landscape. “In June, the farmers take up the first crop taking advantage of the southwest monsoon. Its harvest is celebrated through the Thiruvonam day just like in Kerala,” says K Madhavan, a farmers leader.

Kanyakumari villages boasted of a network of tanks to store the plentiful rains they got and they used to have three crops every year as a routine. “The landscape is such that the rain that pours in the ghats can quickly run off into the sea. To prevent that, waterbodies were dug in every village,” says social researcher Thirparappu Jayamohan. When famine hit in the 19th century, tapioca was introduced and it has remained a part of the local cuisine.

Lazarus says the fishermen here are highly skilled. “The sea is quite rough and challenging in these parts since three oceans meet here, and fishermen are equally skilled. They have to maneuver through currents that can go either direction,” he says.

Lazarus says the fishermen here are highly skilled. “The sea is quite rough and challenging in these parts since three oceans meet here, and fishermen are equally skilled. They have to maneuver through currents that can go either direction,” he says.

Lazarus adds that on surface the current may be north-south, but some 5 m below it can turn south-north. Waves can be routinely 8 feet high and the coast is strewn with big, black rocks. “Kanyakumari fishermen have developed their skills to overcome all these adversities,” he says.

Elsewhere in Tamil Nadu, social reforms were instituted in the late British period, largely as a result of the Justice Party and Periyar. Kanyakumari saw social reform movements a hundred years earlier when it was part of the Travancore kingdom. A leader of the movement was Ayya Vaikundar. Following him, Chattambi Swamigal, Sri Narayana Guru, Ayyankali and others headed social reform efforts. “When Jainism and Buddhism were on the up here, Christianity and Islam came. Though Brahmin domination did reign here, reforms have also been instituted in parallel,” says historian Kollangodu Viswan.

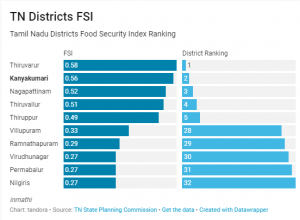

The role of Christian missionaries in spreading education is also to be noted. “Along with their evangelical activities, they expanded education and health facilities,” says Lazarus. He cites Neyyur hospital and Putheri Catherine Booth hospital that were established by missionaries more than 100 years ago. Kanyakumari leads Tamil Nadu in many social indices including the human development index.

As a result of sustained agitations by Ayyankali, Dalits got the right to be educated in 1910 in Travancore state. The seeds of change were sown during that era, says Lazarus.

As a result of sustained agitations by Ayyankali, Dalits got the right to be educated in 1910 in Travancore state. The seeds of change were sown during that era, says Lazarus.

J M Hasan of the Tamil Nadu Progressive Writers’ Association says in Mysore state and Travancore state the rudiments of a democratic set up were there. In Travancore, for instance, through the Sri Moolam Thirunal Praja Sabha, people elected their representatives although there was no universal adult suffrage. When India became independent, Travancore refused to join the Indian Union. Passports were demanded for travel to Tirunelveli. After protests, Travancore became part of the Indian Union.

In 1956, the district was created based on linguistic organization of states. “Kanyakumari was a step ahead of the then Madras presidency in education and social development. This continues to this day,” he adds.

Read in : தமிழ்