Read in : தமிழ்

Epigraphist and archaeologist S Ramachandran has written widely on epigraphy – notably on the upper cloth revolt and the Tranquebar manuscripts, among other topics. His discovery of an anchor, midsea at Tranquebar, with the help of fishermen is considered a milestone in oceanic archaeology. Formally educated in Tamil Literature as well as epigraphy and archaeology, Ramachandran worked for 27 years with the Tamil Nadu Archaeology department until 2005. Since then, he has been writing prolifically, producing not just books but also posts and videos on his website sishri.org.

The veteran epigraphist has published three books, including one on Tamil poet Kannadasan, tracing his oeuvre to heavy influences from Tamil literature. Currently writing a series of articles in Kadambam, a bimonthly literary magazine based in Tiruchi, Ramachandran is also working on a book titled Kaapiya Tholkudiyum and Tholkappiyamum (Ancient Race of the Epic Era and Tholkappiyam).

Epigraphist and archaeologist S Ramachandran

Ramachandran views Tholkappiyam not merely as a grammatical treatise but also a work with a logical approach to the Tamil language. For instance, he says, grammatical terminologies such as ‘ezhuvaai’ (subject), ‘payanilai’ (predicate) and ‘seyappaduporul’ (object) are unique to Tamil.

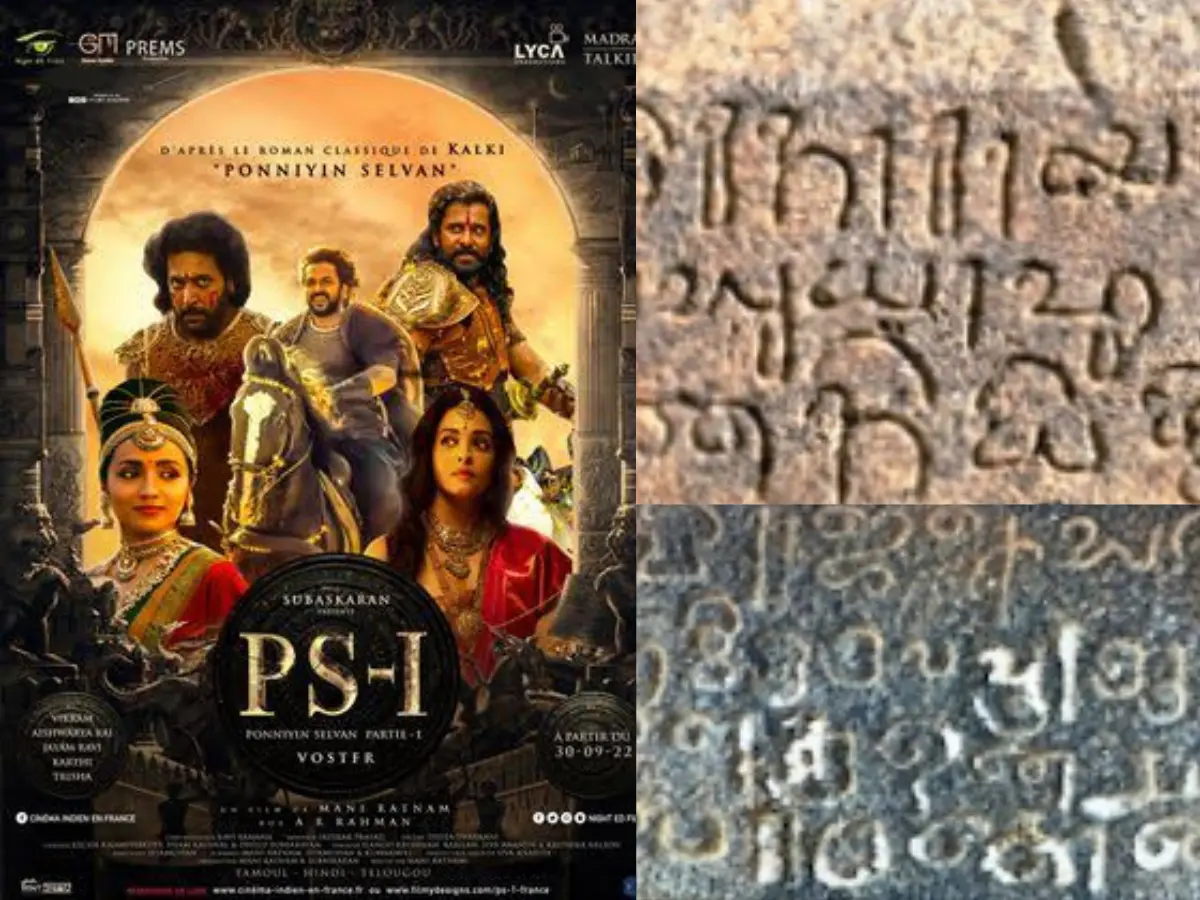

In a chat with him, Ramachandran shares his knowledge about the Chola-era epigraphs and stone inscriptions, and the perceptions that the recently-released film Ponniyin Selvan has created among the public.

Ramachandran considers himself more of a scholar than a bureaucrat although he worked in the government establishment. In fact, he took early retirement voluntarily so that he could work independently, with no red tape to hinder him.

Ramachandran’s discovery of an anchor midsea at Tranquebar with the help of fishermen is considered a milestone in oceanic archaeology

Asked about the reign of Raja Raja Chola being hailed as a golden age in Tamil history, Ramachandran had a different take. “No reign per se can be described as a golden one,” he says. “Perceptions of a golden age differ from person to person. Some people consider the present age of high technological growth as the golden era of human history. We live in the age of democracy where we have the freedom to express our ideas freely, whereas democracy cannot be said to have flourished in olden times, particularly in the period of Raja Raja Chola. But one thing is clear. In terms of arts, literature and architecture, administration and army structures, his reign was extraordinary.”

Talking about the importance of epigraphs in reconstructing the past, Ramachandran says an epigraph is not a literary piece; it is rather a historical document, which in the case of Tamil history reveals facets of its religiously-oriented society.

Also Read: Row over preserving records of Tamil inscriptions ends

Epigraphs were a feature of all kingdoms in the past as they were inseparably intertwined with temples around which Tamil culture revolves.

To the question of whether Raja Raja Chola was a Hindu – a topic that has been abuzz in social media circles since the release of the Tamil film Ponniyin Selvan, based on the novel of the same name – Ramachandran says categorically that he was a Saivite king who patronised Saivite scholars and poets and their works. One of his titles was Sivapadha Sekaran.

The bakthi cult that originated in Tamil Nadu in the 5th or 6th century reached its zenith during the reign of Raja Raja Chola. In those days, temples, mostly Saivite, which were the nodal centre of festivals and ceremonies, featured many epigraphs and stone inscriptions.

Temple rites were classified into three types, Nithyam, Naimithyam, and Kaamiyam.

Nithyam denoted the routine rites of daily worship. Naimithyam outlined special ceremonies held as part of the ruler’s birthday or zodiac sign or birth star. For instance, ‘Sadhayam’ was the constellation that marked Raja Raja Chola’s birth. So, on the day of the Tirunakshatra, special poojas and celebrations were held in his honour. Even now the king’s ‘Sadhaya Vizha’ is celebrated in the Thajavur Big Temple, over 1,000 years on.

Kaamiyam refers to poojas and rites performed as an offering of thanks to the deities for fulfilling the prayers of devotees, including royal personages.

Perceptions of what the golden age is differ from person to person. Some people consider the present age of high technological growth as the golden era of human history. We live in the age of democracy where we have the freedom to express our ideas freely

Talking about the hierarchy of revenue officials during the Chola period, Ramachandran says that revenue collection areas were divided into ‘mandalam’ (zone) ‘naadu’ (country – equivalent to district) and ‘valanaadu’ (big country – equivalent to taluk). The lands were measured accurately using various metrics including ‘angusta pramanam’ (inch) and documented in a fool-proof manner.

Raja Raja Chola’s kingdom being temple-oriented, they also doubled up as treasure-houses of various documents and epigraphs holding, among other things, the details of land measurements, lands donated, lands seized and lands sprawling across the whole region.

Asked about what was famously known in the past as ‘aadhurasalai’ (hospital) during Raja Raja Chola’s reign, Ramachandran says that epigraphs belonging to the periods of Sundara Chola and Rajendra Chola found in the Papanasam region and at Tirumukkoodal near Kancheepuram throw light on how ‘aadhurasalais’ functioned in a tightly built structure. They relied on Ashtanga Hridayam, one of the primary root texts of Ayurveda, for the treatment of diseases. The epigraphs say a lot about the various methods of medical treatment and about medicine, including what was termed as ‘arishtam’ (medicinal tonic for consumption).

Also Read: A prize to honour V. Venkayya, epigraphist who recorded ancient Tamil democracy

Answering a question about the Cholas bringing Brahmins from Uttar Pradesh to their kingdom and the resultant supremacy of Sanskrit and the caste system in Tamil Nadu, Ramachandran says that during the reign of the Cholas, not only the Brahmins but also craftsmen of other communities such as Kammalar from the north India were brought down here. In fact, at the time, there was an interaction of luminaries in law, administration, education, arts and sculpture all over India. Even Greek and Roman craftsmen were brought here.

To say that after Brahmins were brought down to the Chola kingdom, the caste system and the supremacy of Sanskrit were established is not totally true, Ramachandran says. Sanskrit was already in vogue in several kingdoms on the land called India today, he adds.

Answering a question about some yet-to-be-published epigraphs of the Raja Raja Chola period, Ramachandran says the issue is misunderstood. He recalls that the epigraphy section of the Archaeological Survey of India was started in 1880. Since south India had lots of epigraphs and the weather condition was conducive for preservation of manuscripts in Udhagamandalam, the epigraphy headquarters office was located there first. Later, it was shifted to Mysuru after air-conditioning facility was provided.

Every year, the ASI sends its teams to study epigraphs in various places and take estampages (impressions taken on paper) of the stone inscriptions. After reading the epigraphs, each containing over 500 lines, the explorers will condense the content in fewer lines. Then the ‘annual report on epigraphy’ (ARE) will be published. The AREs give us the essential features of the period they belong to.

Very important epigraphs were studied and published in volumes of ‘Epigraphia Indica’, an official publication of the Arachaeological Survey of India. One such stone inscription is the Udayarkudi epigraph, the only one of its kind, which lists the names of conspirators involved in the murder of Adita Karikalan. The Udayarkudi epigraph, which has often been discussed in recent times, lists the assets of the culprits which were given to the temple as ‘nivantham’ (donation).

Historian Neelakanta Sastri in the 1930s or 1940s relied on this Udayarkudi epigraph to raise the question of why it had taken the Chola kingdom 18 years after the murder to initiate action against the culprits. The murder took place in 969 CE and the action was taken in 987 CE, that is, after Raja Raja Chola took over the reins from his uncle Madurantaka Chola.

Sastri’s article about the Udayarkudi epigraph is, however, neither about the manner of Adita Karikalan’s murder nor about the actual murderers. The names it contains were of those connected with the murder. Sastri’s article was published in Epigraphia Indica.

“Besides, 40 volumes of South Indian Inscriptions were published, which contain the replicas of South Indian Inscriptions in full form. But only till 1920 such fully read inscriptions were published. Of course, some inscriptions were published after 1920. But as no strict norms and parameters were followed, lots of complex problems cropped up,” he says.

The Udayarkudi epigraph is the only one of its kind listing the names of the conspirators involved in the murder of Adita Karikalan. The epigraph, discussed often in recent times, lists the assets of the culprits that were given to the temple as ‘nivantham’ (donation). Historian Neelakanta Sastri wrote an article about the epigraph, which was published in Epigraphia Indica

Addressing the current craze for Chola history, Ramachandran says there seems to be a romantic spirit behind the craze. Of course, the period of Raja Raja Chola’s reign had several distinct features such as temples, arts, administration and so on. Yet history being hard and harsh, there is no room for romanticism, as it is portrayed in the novel and the film Ponniyin Selvan, he says.

While the Big Temple in Thanjavur speaks volumes about the astronomical skill, aesthetical tastes and amazing peak of the Chola period, where technocrats, scholars and talented administrators flourished, one cannot deny that the wars the Chola kingdom waged inland and abroad left a trail of destruction, the impact of which was felt for centuries later. The social systems, religious in nature, which were scrupulously followed during the Chola period may seem backward in hindsight. But they were built into the kingdom, having been passed on through generations.

Asked about what scope epigraphy could have in the 21st century job market, Ramachandran exuded optimism that tourism being an evergreen money-spinning field, epigraphists’ role in the sector can hardly be underestimated. So, it can be pursued as a lucrative discipline, he says.

As for women’s role and scope in epigraphy, he says he was not competent enough to assess the role and scope of women in the field. Yet, as happens in all fields, women can surely come up in epigraphy too, just as anyone who pursues anything passionately. He cited the example of epigraphist Vasanthi being a top official in the department. Of course, there are challenges that women epigraphists face in the field that their counterparts in other spheres face as well. He says there was one instance in Gangaikonda Cholapuram where a woman official had to face off with locals regarding some issues.

Ramachandran hopes that more scholars take to epigraphy, so that the history of Tamil Nadu told vividly through stone inscriptions can be elaborately studied and recorded.

Read in : தமிழ்