Read in : தமிழ்

It is not every day that you spot the elusive Niligiri Tahr on the slopes of the Varaiattumudi hill, one of the most picturesque landscapes of the Kanniyakumari forests. The treacherous trek up the grassy peaks and shola forests leads you to the enchanting lair of the Varrai-aadu (the word for Nilgiri Tahr in Tamil, which literally means ‘goat of the cliff’), leaving a memory to cherish.

Apart from a few rare visits by tourists from the plains, the misty hills of Mahendragiri, Tiruvannamalaimottai, Varaiattumudi, Muthukuzhuvayal and Kilavarai are mostly pristine. The sanctuary is a sprawling patch of wilderness located at the southernmost tip of the Western Ghats, within the state of Tamil Nadu. It shares its boundary with Neyyar wildlife sanctuary of Kerala in the north and Kalakad – Mundathurai Tiger reserve of Tamil Nadu in the north-central east.

All other sides are bordered by rubber plantations or revenue lands. The forest is also a source of the Kodayar, Paralayar, Pazhayar and Valliyar rivers that nourish the southern-most districts of Tamil Nadu. The sanctuary is rich in biodiversity with several microhabitats and is also home to the indigenous Kani community.

In search of the sure-footed ungulate

The Nilgiri Tahr,a sure-footed ungulate, that inhabits the open montane grassland habitats at elevations from 1200 to 2600 metres of the South Western Ghats, dwells in this ecological wonder. Currently, the Nilgiri Tahr distribution is along a narrow stretch of 400 km in the Western Ghats between Nilgiris in the north and Kanniyakumari hills in the south of the region. Not much was known about its population and distribution until the first extensive on-ground Nilgiri Tahr survey was undertaken by the Tamil Nadu and Kerala forest departments in 2008.

Treading the terrain of the sure-footed ungulate is no cake walk, as it can be taxing physically and daunting mentally.

WWF-India took active part in the survey and ever since has been regularly doing a periodical assessment of the Tahr and its habitat. As per the last survey in 2015, about 3000-odd individuals were estimated to be distributed across this narrow stretch of land.

The present survey, which we were a part of, started in early 2021 and gave us new insight into the behaviour and population of these protected ungulates.

Clambering rocky cliffs

My excitement to spot one of the Nilgiri Tahr made me climb the steep and poky edges of the Varaiattumudi hills, some of which were jutting out in a manner where we had to literally crawl on fours to go across the rocks. The tiring journey will however seem worth once one reaches the top of the grassy escarpment, where we could scan the surrounding peaks for the presence of the elusive tahr. Treading the terrain of the sure-footed ungulate is no cake walk, as it can be taxing physically and daunting mentally.

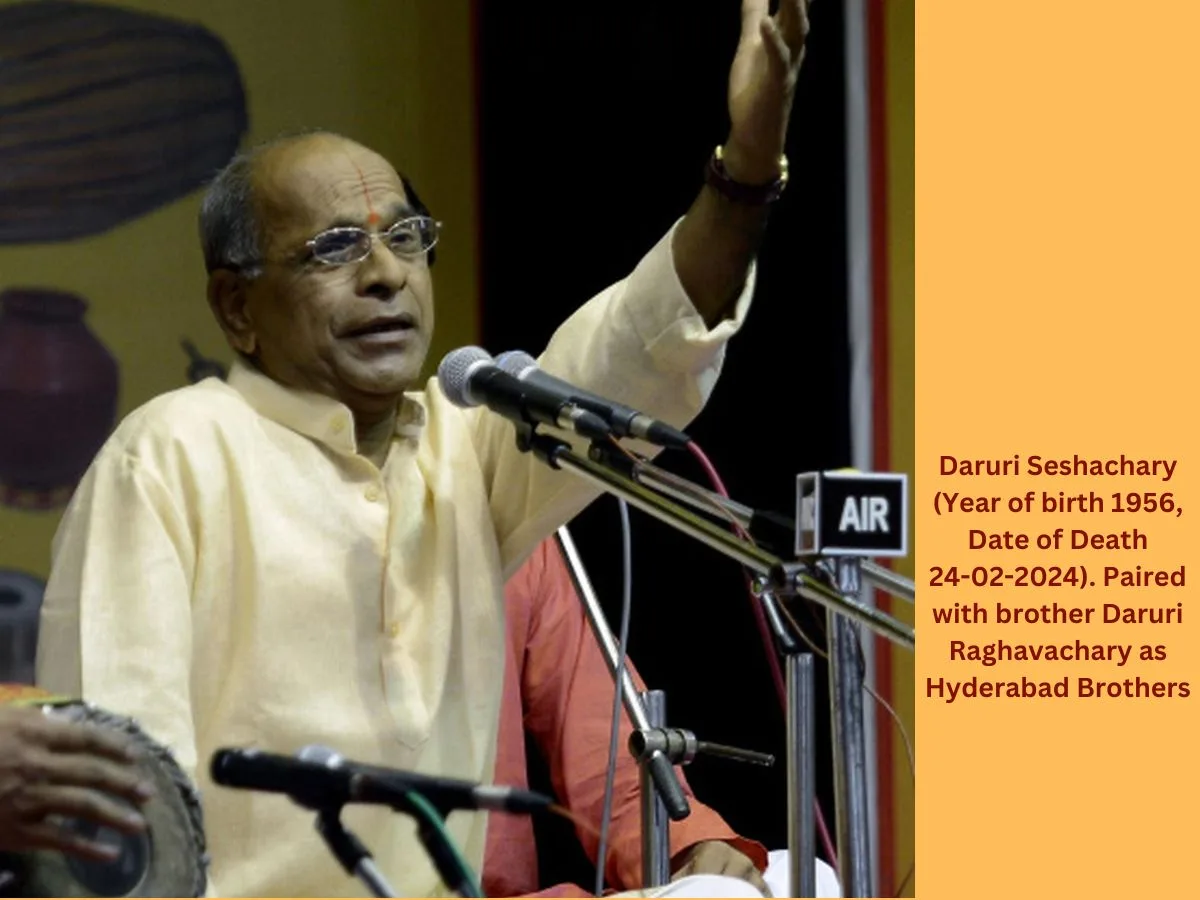

Nilgiri Tahr survey team negotiating the cliffs to reach the mountain top to survey for Nilgiri Tahr

While our team sat under one of the mountain date palm (Phoenix loureiroi) tree for a quick break after the tiring climb, I could do nothing but to admire the beauty of the ancient mystic hills. The blue horizon keeps you hooked to it as if it has cast a spell on the eyes. This however did not last for long as one of our team members spotted a massive Indian Gaur that happened to be climbing up from the opposite slope. The bovine is typically unfriendly to inquisitive humans like us. For a few minutes, our weary eyes followed the shimmering purple coat, before it decided to take a turn and head elsewhere and we heaved a sigh of relief.

Sighting the tahr

We quickly scanned the edges of the ridge for signs of the tahr and spotted pellets scattered over the grassy landscape. The size of the pellets indicated there was a herd with young ones travelling along with it. We didn’t have to look for them much longer as our luck favoured us with the sight of a herd of about 30-odd individuals. As the name of the peak suggests, it is indeed a lair of the Varrai-aadu.

After taking down the necessary notes, we decided to begin our descent along the slopes of the hill. This time lady luck decided to snigger back at us and opened up the skies to a steady drizzle.

Soon, sheets of mist wafted past us in the wind and visibility took a hit. Battling incessant rains, slimy leeches scaling up our shoes and a tough terrain, we clambered up the summit of the next set of hills with rolling grasslands, that connects with Kerala on the western side.

Signs of predators

It seemed that some mysterious hand had decided to open up the clouds to drench us clean before we could have a view of the exhilarating landscape. The sun soon shone bright and little brooks started trickling down the green slopes.

There seemed to be a presence of a leopard as scats and pugmarks indicated so. As we trekked further, we sighted a couple of tahrs in the distant grasslands. Perched precariously on the side of a vertically steep cliff, a small herd of three, including a lamb, nibbled at the moss on the rocks.

Protecting the Nilgiri Tahr would also mean protecting the grassland-shola habitat that it inhabits which is refuge to many other smaller species of mammals, reptiles, amphibians, birds and insects.

Having trekked over seven kilometres on the day-one of our three-day survey, we took refuge in a cavern for the night. We heard the intermittent growl of a sloth bear that had presumably had a litter recently.

Anthropogenic pressures

The second day began with the sighting of a herd of seven tahrs in a different area of the sanctuary. We had to quickly take note of the age, sex and activities along with the GPS reading as part of the survey, before they disappeared. Apart from taking pictures, various details of the sighting along with the anthropogenic pressures that we come across, are recorded in the survey sheet, as a part of the estimation.

Due to the elusive nature of the species, the difficult terrain that it inhabits and the hostile weather conditions of the mountains for most of the year, surveying Tahr populations is a challenging task. However, these surveys have helped us get a first-hand understanding of the ecology of the species apart from determining the current population status and the natural and anthropological pressures that this species face. Synchronised surveys across Tahr habitats in Kerala and Tamil Nadu at least once in two years has been helping us map and address the challenges in tahr conservation. The next two days went about in a quite expected manner as we travelled back to our city lives leaving the tahrs at their paradise.

Grassland-shola habitat of Varaiadumudi

Protecting the Nilgiri Tahr would also mean protecting the grassland-shola habitat that it inhabits which is refuge to many other smaller species of mammals, reptiles, amphibians, birds and insects. This unique ecosystem harbours all the rain water and releases continuously throughout the year to form numerous small streams that join together to form rivers. Nilgiri Tahr conservation therefore is not just about survival of this majestic species, but it’s about the future of water security of the southern states.

(The author is Project Officer, WWF-India. The article has been edited by A Shrikumar, Senior Communications Officer, WWF-India)

Read in : தமிழ்