Read in : தமிழ்

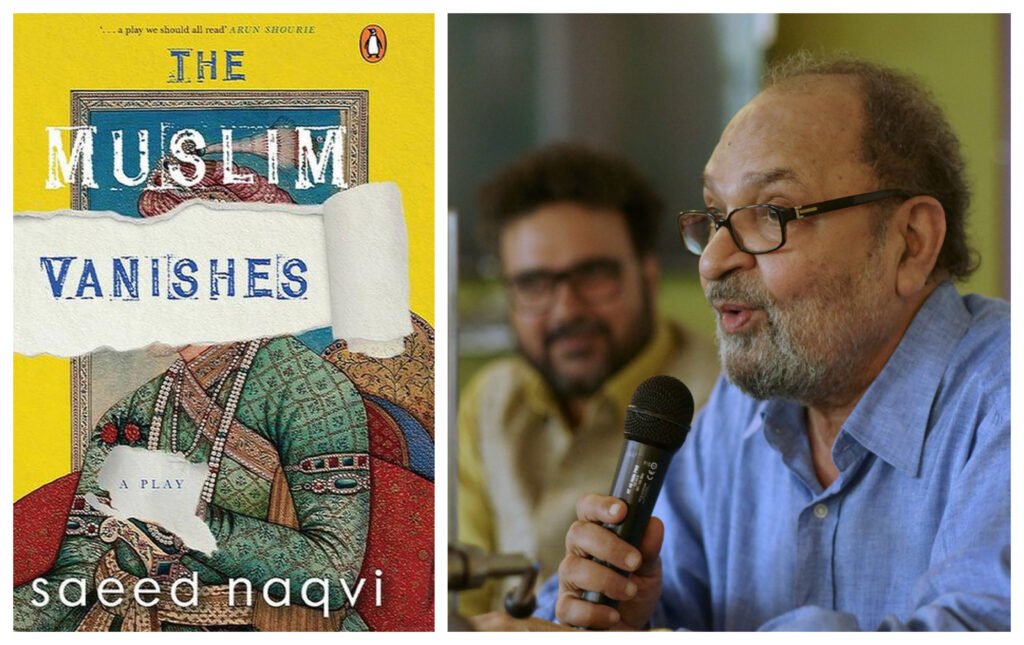

Muslim-mukt Bharat. OMG. How succinctly, devastatingly put. The flip side: you lose Muslims, and well, the Dalits and MBCs/OBCs are upon you. Catch 22 indeed. This is the premise of Saeed Naqvi’s recently published play The Muslim Vanishes.

Having been used to a relative measure of communal harmony in the south, the Hindu-Muslim tensions up north might be difficult to wrap our heads around. Even the deadly blasts of Coimbatore in 1998 and the odd strife here and there have not made the Hindus of Tamil Nadu look at Muslims with instinctive hostility. But it is a horrid fact of life north of the Vindhyas for a variety of reasons, and politicians make it a big deal—Modi or Yogi, even godmen and women—by relentlessly demonizing Muslims. It is in this context that Naqvi’s play should be seen and appreciated.

The play searingly captures a ghastly fantasy of the ‘cowlanders’: By some miracle all the Muslims of India vanish, yes, are gone for good – whereto, none seems to know. With them goes Qutub Minar too! And a little later the Urdu language itself, all the Urdu words in use in daily life. The Musalman is gone without a trace.

But when the wildest dream of the Hindu fanatics is fulfilled, follows in its trail chaos too, as the lower castes take over everything left behind. As the upper caste liberals despair, savants of the past are brought together to suggest a way out of the avarna-savarna impasse. No way out of course. Muslims go and with them even the notional democracy we live under, Naqvi seems to suggest.

The rich contributions of Muslims to Hindustani music and a long list of Hindu poets who wrote in Urdu, poignantly reminisced, give us a glimpse of Naqvi, the culture historian, a rarity even among his contemporaries.

The former journalist’s mastery of the history of Hindu-Muslim relationship is indeed formidable. Actually, one is overwhelmed.

Of the Muslims who went to Pakistan after partition, nearly 20,000 returned. The properties they had vacated had been taken over in many cases, leaving them to fend for themselves. The government didn’t go to their rescue, And the Hindus were encouraged to return from East Bengal, but not the Muslims from West Pakistan—thus in the times of Nehru himself.

The rich contributions of Muslims to Hindustani music and a long list of Hindu poets who wrote in Urdu, poignantly reminisced, give us a glimpse of Naqvi, the culture historian, a rarity even among his contemporaries. “Here’s Baba Allauddin Khan’s room. Notice the paintings of Goddess Saraswati on the wall. There’s also a prayer mat facing the Kaaba.” The scene cuts to a temple. “And here is the Sharda Ma temple where Allaudin Khan went every day to seek the blessings of Goddess Saraswati….” How much has the Modi raj ruined it all for us?

Much of the play is acted out in TV studios, a bit irritating that. Yet Naqvi sahib could have thought of a few more contrivances to say what he wanted to.

One major flaw in this otherwise fascinating play is that the Shah Bano case, to which the current horrors can be traced with justice, doesn’t even find a mention, and the appeasement politics is sought to be glibly explained away.

One major flaw in this otherwise fascinating play is that the Shah Bano case, to which the current horrors can be traced with justice, doesn’t even find a mention, and the appeasement politics is sought to be glibly explained away.

As I have remarked earlier too, Saeed Naqvi turned an apologist of sorts over a period of time. In his glorious Indian Express days he was a no-nonsense secularist, calling out fanatics anywhere and everywhere. But injustice done to him by Ramnath Goenka, and the subsequent straits he found himself in apparently embittered him a lot. Note Arun Shourie’s commendation on the book wrapper. That is some irony indeed. It was he who did Naqvi in—their rivalry was famous those days.

Incidentally as editor of the southern editions of The Indian Express, Saeed Naqvi made waves in the eighties. Those used to the soporific spiel of The Hindu and its clones found The Indian Express under Naqvi a refreshing change. He was threatening to change the very face of journalism, but it was not to last. In less than a decade, he was shunted off to Mumbai by Shourie to serve as a special correspondent. He left print journalism in disgust, never to come back, except for the columns he writes here and there. In one of his interviews, Naqvi claimed that only because he was a Muslim could he never make it as an editor. He had very much been in the race for Hindustan Times, but was ignored.

Whatever be the truth of his claims, the fact remains that in his heyday Saeed Naqvi was one of the finest writers of English in the Indian media, and with an amazing range at that. He was also a man of great ideas, and dazzling in understatement, never going at his targets with a hammer or a bludgeon. “You must make them squirm, leaving them in a dilemma how to react,” he would say.

The superb technique is seen in all its glory in this play.

Read in : தமிழ்